Como as ideias de Edward de Bono estão a transformar as escolas

Por Rachel Pugh

29 Janeiro 2009

Put your thinking hat on: How Edward de Bono's ideas are transforming schools

Teaching children how to think has brought academic success to schools in Manchester. But will techniques pioneered by the guru Edward de Bono catch on?

Rapt in thought, the four-year-old is taking part in a discussion about improving playtime. With a scowl of concentration, he clutches on to Patsy, the black-hatted teddy, and says: "A football hit me in the face once."

This is the reception class at Ditton Primary School, near Widnes, and the teacher, Jackie Timmis, has asked him about the negative aspects of football.

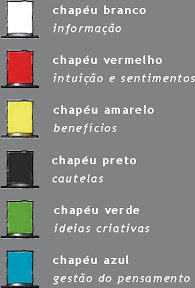

His classmates have already made it clear they recognise what facts are – it is what Fred, the white-hatted teddy, encourages. Red-capped Fifi puts them in touch with what they feel about an idea. Patsy is fixed on the negatives, yellow-clad Hal on the positives, while cuddly Ivor is as fertile with creative ideas as his green hat. Blue-hatted Bella is "the boss" organising their thinking.

They don't know it, but they are using Edward De Bono's structured thinking technique, the Six Thinking Hats, that colour codes different ways of tackling a question, to give them a framework for problem-solving and exploring ideas. The hats have been turned into teddies, given the pupils' age.

These are advanced concepts for such young children but Ditton Primary is an accredited Thinking School, committed according to the head teacher, Carol Lawrenson, to creating "little thinking creatures".

This scene at Ditton may be played out in classrooms across the UK in the next few years, if thinking guru Edward de Bono succeeds in introducing the key concepts of his thinking framework, the Six Thinking Hats and lateral thinking, into the national curriculum.

The Edward De Bono Foundation has just set up the world's first university-based Centre of Serious Creativity and Constructive Thinking at Manchester Metropolitan University's Crewe campus. And Ditton is an exemplar school. Manchester Met is the largest university for the teaching of education in Europe, so work has already begun to teach academics De Bono's concepts via four-day courses in order to disseminate this to teachers. Manchester's academies are already showing significant interest in taking on the concepts.

Chief executive of the De Bono Foundation UK, Bob Rawlinson, is passionate about the need for a change from what he considers an overly Socratic to a more creative approach to thinking and learning in schools. "All my life I've believed in the development of people to get the best out of them," he says. "I believe passionately that this should be done at the earliest possible age to inspire children to achieve."

Research evidence obtained by the De Bono Foundation suggests his tools can have a positive impact on academic achievement and behaviour. As part of the Government's New Deal job-finding programme, teaching youngsters the De Bono thinking systems for only six hours improved their employment rate by 500 per cent.

Ditton Primary has been using the De Bono methods for the past six years alongside several other thinking methods – Hyerle's Thinking Maps, Art Costa's Habits of Mind and Spencer Kagan's Co-operative Learning – powered by Carol Lawrenson's vision to turn out children equipped to think for the 21st century: "We want our children to be respectful, responsible, resourceful, good creators and successful in whatever intelligences they show," she says. "That is more important than success in Key Stage 3."

Her school in one of the most deprived boroughs in the country, is also always in the top 15 per cent of primaries in the country for academic results. Bullying is rare and there have been only 11 disciplinary incidents since February 2008. Before the introduction of the thinking tools that figure would have represented a half term.

Traditional subject areas have been thrown out. Thinking books replace exercise books. The curriculum is taught entirely in seven themes such as problem solving and reasoning, creative development or knowledge and understanding of the world. But all subjects are taught with creative thinking tools at the fore. Images of the coloured hats crop up all over the school and lessons are peppered with references like "let's apply some green hat (creative) thinking" or "White hats on – what are the facts?" At the end of 2008, Ditton and two other nearby nationally-accredited thinking schools formed a consultancy – Halton Thinking Schools (HATS) – to train other schools.

According to Professor Chris Husbands, of London's Institute of Education, research evidence confirms the importance of teaching thinking. Ten years ago, the national curriculum gave few opportunities to teach it, not so now. He cautions, however: "The most important thing in determining the quality of education is the quality of teaching."

Thinking tools may be a way to improve teaching, but they are very time-consuming in the classroom. Their use is easier in primary schools, but in high schools they only work when incorporated into subjects by committed teachers, says Husbands.

This is what has happened at St Ambrose Barlow Roman Catholic High School in Swinton, Salford, which achieved 88 per cent A*-C passes at GCSE despite having many pupils from deprived homes. It has been designated a National School of Creativity – only the second in the North West.

The head teacher, Marie Garside, has overseen the introduction of a number of thinking tools including De Bono's across all year groups, for several years. The Thinking Hats add power to thinking across the curriculum on issues such as the destruction of the rain forest but the school also used it to work with Salford Council on plans for the regeneration of the deprived area of Langworthy. Eighty six per cent of pupils go on to post-16 education.

"The impact on the school of using these tools is that we now have more confident learners," she says. "Children need a completely new set of skills to deal with data than they did when I started teaching 33 years ago. I want to produce thinkers, not exam fodder."

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário